The Electrical Atom

{Keith Dixon-Roche © 07/08/23}Introduction

This work was initiated due to the discovery that the proton-electron pair and Newton-Coulomb atom may be used to predict the electrical properties of elemental matter; Voltage (J/C), Current (C/s), Resistance (J.s/C²), Resistivity (J.s.m/C²), etc..

The purpose of this study is to answer the following questions:

1) Can the Newton-Coulomb atomic model be used to predict the electrical properties of elemental matter using mathematics?

2) Can the Newton-Coulomb atomic model be used to predict the electrical resistivity of elemental matter using mathematics?

Note: The essential constants and mathematical symbols are provided at the bottom of this page.

Conclusion

The answer to both the above questions is yes!

Not only is it now possible to describe the mechanical (or magnetic) characteristics of elemental matter using the mathematics of the Newton-Coulomb atom, but it is also possible to describe its electrical properties mathematically using the same model ...

... providing yet more evidence that the Newton-Coulomb version is the correct atomic model.

However, the temperature effect of structural changes to elemental matter, which alters temperature coefficients from linear to non-linear, may make mathematical predictions (using any atomic model) a little more challenging.

Electrical vs Magnetic

Due to the coupling ratio, the electrical (not the magnetic) charges unite all proton-electron pairs.

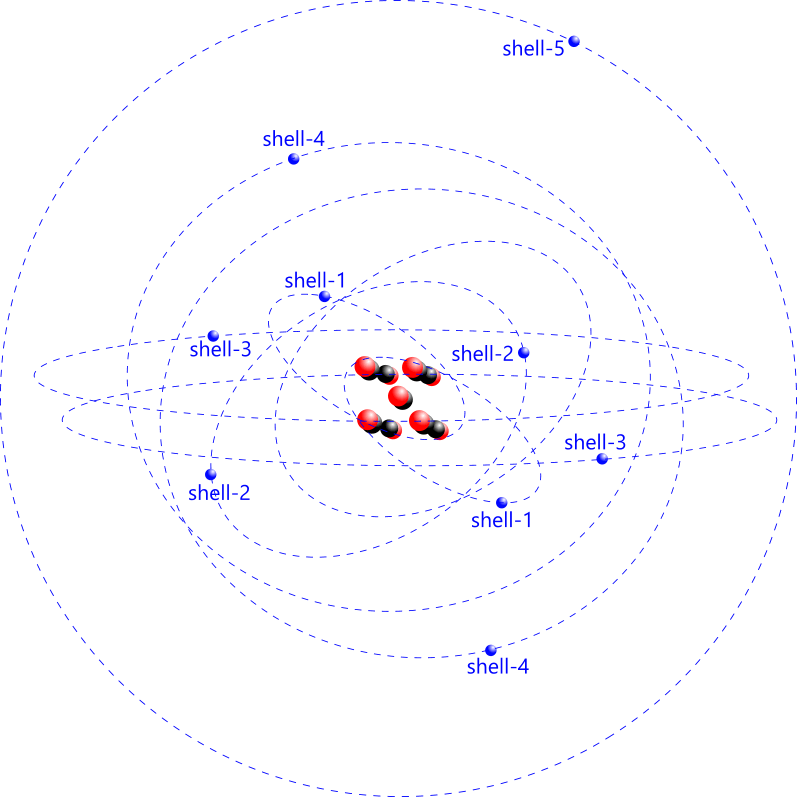

The electrical particle charges - positive (protons) and negative (electrons) - repel and attract to maintain balance within atoms. Contrary to popular belief, proton-neutron partners do not sit together in atomic nuclei, but are forced apart and oriented (within the atom's innermost shell) in a structural pattern that ensures all proton charges are neutralised (protected) by their neutrons (Fig 1). This pattern is called a lattice structure, and is replicated in atomic collections as elemental matter in both gaseous and viscous conditions; it is responsible for Dalton's law.

The magnetic field generated by each proton-electron pair holds adjacent atoms together as viscous matter, and the electrical charges held by the proton partners push them apart. The magnetic field is therefore responsible for the density of elemental matter and the respective inter-atomic forces (Fₑ & Fₘ) define their viscous-gas condition; transition occurs when the repulsive electrical charge and attractive magnetic field forces are equal; Ṯg: Fₑ = Fₘ.

The density of an atom is that of all the proton-electron pairs - and their neutron partners - within its outermost shell.

The measured gas transition temperature - that of the proton-electron pairs in shell-1 - of elemental matter is that above which, the magnetic field forces are no longer able to resist the inter-atomic [proton] electrical repulsion forces.

Operational electrical current (electron flow-rate) through elemental matter (conductor) occurs when the electrons in its atom's outermost shells are pulled from their orbits.

Voltage (V)

Voltage is measured in Joules per Coulomb, which means the potential energy in an atomic proton-electron pair.

The potential energy in a proton-electron pair is defined by its temperature (Ṯ), and calculated thus: PE = Ṯ.kB' {J}.

The electrical charge in an electron is the elementary charge unit (e) {C}.

Therefore, the Voltage in a proton-electron pair is calculated thus: V = PE/e {J/C}.

For example; the potential energy in the outermost proton-electron pairs of a tungsten atom at a temperature of 300K is:

PE₃₇ = 8.108108108 x 1.31347656477524E-22 = -1.064980998E-21 {J}

and the voltage in this proton-electron pair is;

V₃₇ = -1.064980998E-21 ÷ 1.60217648753E-19 = -6.64708917082E-03 {J/C}

This is therefore the minimum voltage you need to apply to an electrical conductor in order to generate electron flow between atoms @ 300K.

However, as long as the applied Voltage is greater than this, electrons will flow between atoms according to its magnitude (e.g. 240V).

Current (I)

Electrical current is the rate at which electrons travel between adjacent atoms in elemental matter due to an applied Voltage (V), which may be calculated like this:

electron velocity: v = √[ ½ . V.e/mₑ ]

Note: V = PE.e; KE = ½.PE = ½.mₑ.v²

electron frequency: ƒ = v/d

Note: 'd' is the inter-atomic spacing

Current: I = e.ƒ

For example; the current in a tungsten conductor due to a Voltage of 240V:

v = √[ ½ . V.e/mₑ ] = 4594107.563 {m/s}

ƒ = v/d = 1.82601E+16 {/s}

Note: 'd' in viscous tungsten is 2.51592039E-10 {m}

I = e.ƒ = 0.0029255978 {C/s}

Resistance (Ω)

Electrical resistance in an atom's outermost proton-electron pair is that required to extract the electron from its proton partnership. It is calculated like this:

e.g. tungsten (shell 37);

Ṯ₃₇ = Ṯ/37

PE = mₑ.v² = mₑ.Ṯ₃₇/X

ƒ = (Ṯ₃₇/Ṯₙ)¹˙⁵ / tₙ

Ω = PE₃₇ / ƒ.e²

which varies with temperature.

Once removed, however, resistance is simply the applied Voltage divided by the operating current; Ω = V/I, which appears to be independent of temperature, which is not quite correct!

For example; the minimum resistance in a tungsten atom @ 300K :

Ṯ₃₇ = Ṯ/37 = 8.108108108 {K}

PE₃₇ = mₑ.v² = mₑ.Ṯ₃₇/X = 1.06498100E-21 {J}

ƒ₃₇ = (Ṯ₃₇/Ṯₙ)¹˙⁵ / tₙ = 2.51203776E+10 {/s}

Ω₃₇ = PE₃₇ / ƒ.e² = 1.65156241E+06 {J.s/C²}

This resistance, which falls with rising temperature, is not a reflection of the influence of temperature on an operating current through a conductor.

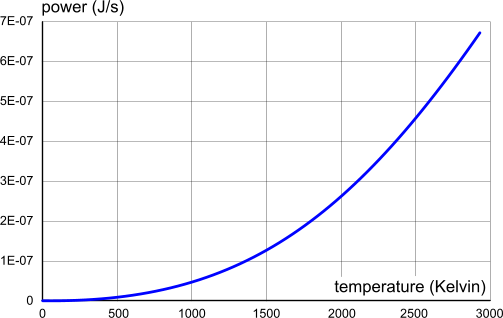

Fig 2. Electrical Power vs. Temperature (proton-electron pair)

Power (P)

Electrical power is the rate at which potential energy is consumed or expended, e.g. Joules per second;

P = V.I = PE/e . e.ƒ {J/s}

For example; the power in the outermost proton-electron pair of a tungsten atom is:

P₃₇ = V₃₇ x I₃₇ = 2.67527248E-11 {J/s}

Note: I₃₇ = e.ƒ₃₇

Temperature

The temperature of the outermost proton-electron pair in any atom may be determined thus; Ṯᴺ = Ṯ/N

Note: N = outermost shell number

The potential energy in a proton-electron pair may be determined thus:

PEᴺ = mₑ.Ṯᴺ/X

which means that the minimum voltage required to generate electron flow in a conductor will increase with rising temperature.

For example, the minimum Voltage required to generate electron flow in a tungsten conductor:

V = PE₃₇/e

@ 300 K: V = 0.0066470891737 {J/C}

@ 2884 K: V = 0.063900683923 {J/C}

Therefore, the higher the atomic temperature, the greater will be the minimum Voltage required to generate electron flow (electrical current).

But this is not the reason for high temperatures due to applied voltages.

For example a tungsten filament @, say, 300 K:

Voltage: V = 240 {J/C}

Current: I = 0.625 {C/s}

Power: = V.I = 150 {J/s}

Electron transmission velocity; v = √[½.240.e/mₑ] = 4.59410756E+06 {m/s}

which represents a total equivalent transmission temperature; Ṯₜ = X.v² = 146375.79661461 K

which must be shared between all the electrons in its new parent atom.

Total temperature in all of a tungsten atom's electrons @ 300K; Ṯₜ₃₀₀ = 2 . ₁Σ³⁷ Ṯᴺ = 2520.95173429K

Note: 2 because there are two electrons per shell

The temperature variation in each electron; δ = Ṯₜ/Ṯₜ₃₀₀ = 58.0637045222

The highest measured temperature of the atoms in the tungsten filament (in its core) will be; Ṯ = 300 . δ = 17419.11136 K

This is the core temperature of all operational electric light-bulb filaments, irrespective of applied Voltage.

Power and filament dimensions are designed to ensure a surface temperature of 2884 K, which gives the correct core temperature for 'white light' (refer to the light-bulb).

Resistivity (ρ)

Electrical resistivity is a moment of resistance, and is measured in 'resistance.metres', and its units of measurement are J.s.m/C².

In an electrical conductor, it is calculated like this: ρ = Ω . A/ℓ

Atomic resistivity: ρₐ = Ω . d² / 2πR

Note: electrical resistivity in viscous matter rises with increasing temperature because; whilst inter-atomic spacing (d) does not vary significantly, electron orbital radii (R) decrease with increasing temperature.

As can be seen in Table 1 (above), the average error between calculated and documented values (1.1) is as close as can be expected given the defective nature of documented values.

And the following comparison between common electrical conductor elements is also reasonable, apart from gold which appears to offer better electrical conductivity than silver and copper.

| Element | Documented | Calculated | error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper | 1.69 | 4.73 | 2.8 |

| Silver | 1.63 | 4.79 | 2.94 |

| Gold | 2.44 | 3.69 | 1.51 |

| Iron | 9.7 | 10.16 | 1.05 |

| Tungsten | 5.65 | 7.33 | 1.3 |

| Aluminium | 2.7 | 8.7 | 3.22 |

| Table 2: Comparison values for common electrical conductors | |||

Discussion

Refer to our dedicated web page for a detailed explanation of the electrical resistivity of elemental matter.

The following Table provides the properties, including electrical resistivity, of various GEC tungsten filaments (page 12) compared with theoretical values:

| Power (W) | Diameter (m) | Length (m) | A/ℓ (m) | Ω (J.s/C²) | GEC ρ (J.s.m/C²) | ρ (J.s.m/C²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 3.00E-05 | 0.56 | 1.2622E-09 | 576 | 7.2705E-07 | 5.270413E-07 |

| 40 | 3.30E-05 | 0.38 | 2.2508E-09 | 360 | 8.1028E-07 | 5.270413E-07 |

| 60 | 4.60E-05 | 0.53 | 3.1357E-09 | 240 | 7.5256E-07 | 5.270413E-07 |

| 75 | 5.30E-05 | 0.55 | 4.0112E-09 | 192 | 7.7016E-07 | 5.270413E-07 |

| 100 | 6.40E-05 | 0.58 | 5.5465E-09 | 144 | 7.987E-07 | 5.270413E-07 |

| 200 | 1.02E-04 | 0.72 | 1.1349E-08 | 72 | 8.1713E-07 | 5.270413E-07 |

| Table 3: GE Filament Resistivity based upon filament dimensions vs. atomic performance 120 Volts and operating temperature (≈2884K) Calculation Method: dimensional: ρ = V²/P . A/ℓ; atomic: Ω . π.d²/R . √[ṮN/Ṯg] | ||||||

It should be noted that the theoretical value is based upon a linear temperature coefficient of resistivity, whereas GEC's values, the mean of which is 7.7931E-07, are based upon the filament's physical dimensions and specified power rating.

NBS (National Bureau of Standards) documented value for the resistivity of tungsten at 2873K is expected to be 8.7E-07 J.s.m/C², but the linear interpretation should be ≈6.6E-07 J.s.m/C². It is considered therefore, that these discrepancies in the tested and specified values are due to the alloyed nature of the respective materials.

In other words, when compared with the expected resistivity value 6.6E-07 J.s.m/C²;

GEC's dimensional value is 18.08% greater,

theoretical value is 20.15% lower,

NBS value is 31.82% greater.

In reality, if GEC's filaments are tungsten alloys, which is the norm, their resistivities should be considerably greater than the theoretical values, which is indeed the case.

NBS's tested values for tungsten reveal a non-linear variation in resistivity with temperature which appears to indicate that the structure of elemental matter varies with temperature. And because resistivity variation is due to dimensional distance between adjacent atoms, it is highly likely that tungsten's actual temperature coefficient of expansion is also non-linear.

However, whilst the mathematical prediction of electrical (and dimensional) variation with temperature is possible, and in fact simple, it is considerably more difficult to include the non-linear effects of structural changes to the elemental matter.

Table 1 shows the calculated (theoretical) resistivity values for all the elements (0 to 92) based upon the above formula. You will have noticed that there is a difference between most of them and the documented (experimental) values. However, given the issues with experimentation in terms of materials, environment and equipment, along with the unreliability of many documented values, these differences are understandable.

Newton-Coulomb Atomic Model

Let's say we want to calculate the operating temperature of a conductor with an applied voltage and resultant current using the Newton-Coulomb atomic model.

Given that the outermost electrons of an atom are transmitted by the applied Voltage, their properties in - say an iron atom - at a measured temperature of 300 K may be defined thus:

Ṯ₁₃ = Ṯ₁/13 = 23.0769231 K

v₁₃² = Ṯ₁₃/X = 57684.0141393 m/s

PE₁₃ = mₑ.v₁₃² = mₑ.Ṯ₁₃/X = 3.0310998E-21 J

As there are two electrons in an iron atom's outermost shell, the potential energy (pd) required per atom is;

V = 2.PEˢ/e = 0.0378372768 J/C

A commercially available product (torch), has the following specification:

I = 4500mAhr = 4500 / 1000 / 3 / 3600 = 4.16667E-04 C/s

Note: '3' quoted for a 3-hour operational life

V = 3.7 J/C

Whereas the expected (calculated) current is as follows:

Electron velocity (between adjacent atoms); v = √[½ . V.e/mₑ] = 570422.1752 m/s

Note: '½' because there are two atoms in an iron atom's outermost shell

Electron frequency; ƒ = v/d = 2.50068088E+15 /s

Note: 'd' is the inter-atomic spacing in an iron atom (2.281109866E-10 m)

Expected current: I = e.ƒ = 4.0065321E-04 C/s

The kinetic energy in the electrons travelling between atoms; KE = ½.V.e = 2.96402650E-19 J

This heat energy in the conductor's atoms will be shared between all of its shell-electrons, thus;

ΣṮ = 2.KE/mₑ . X = 4513.25372895 K

Measured temperature increase in the conductor; δ = ΣṮ / (2.ₛ₁Σˢ¹³ Ṯ₁) = 2.365337476

Therefore, the temperature of the active conductor will be Ṯₒₚ = δ . 300 = 709.6012427 K

Yet further verification of the Newton-Coulomb atomic model.

Essential Constants & Mathematical Symbols

Essential Constants

The primary and principal constants you need to calculate the electrical properties in elemental matter are listed below:

ξₘ = 1836.15115053207

e = 1.60217648753E-19 {C}

tₙ = 5.90596121302193E-23 {s}

Ṯₙ = 623316124.717178 {K}

c = 299792459 {m/s}

PEₙ = 8.18711122262534E-14 {J}

kB = 1.38065156E-23 {J/K}

kB' = 1.31347656477524E-22 {J/K}

X = 6.9353271647894E-09 {K.s²/m²}

Xᴿ = 1.75646616508035E-06 {K.m}

Mathematical Constants

t = electron orbital period {s}

ƒ = electron orbital frequency (1/t) {/s}

g = potential acceleration (proton-electron pair) {m/s²}

m = mass {kg}

N = shell number

PE = potential energy (proton-electron pair) {J}

R = electron orbital radius {m}

Ω = electrical resistance {J.s/C²}

Ṯ = temperature {K}

v = electron orbital velocity {m/s}

ρ = resistivity {J.s.m/C²}

ψ = RAM/Z (neutronic ratio)

ℓ = conductor length {m}

Ø = conductor diameter {m}

A = cross-sectional area of the electrical conductor {m²}

Subscripts

Subscripts:

ₐ atomic

ₑ electrical

ₘ magnetic

N means shell number

ₛ shell number

₁ shell number 1 (innermost shell)

Further Reading

You will find further reading on this subject in reference publications(69, 70, 71 & 73)