The State of Matter

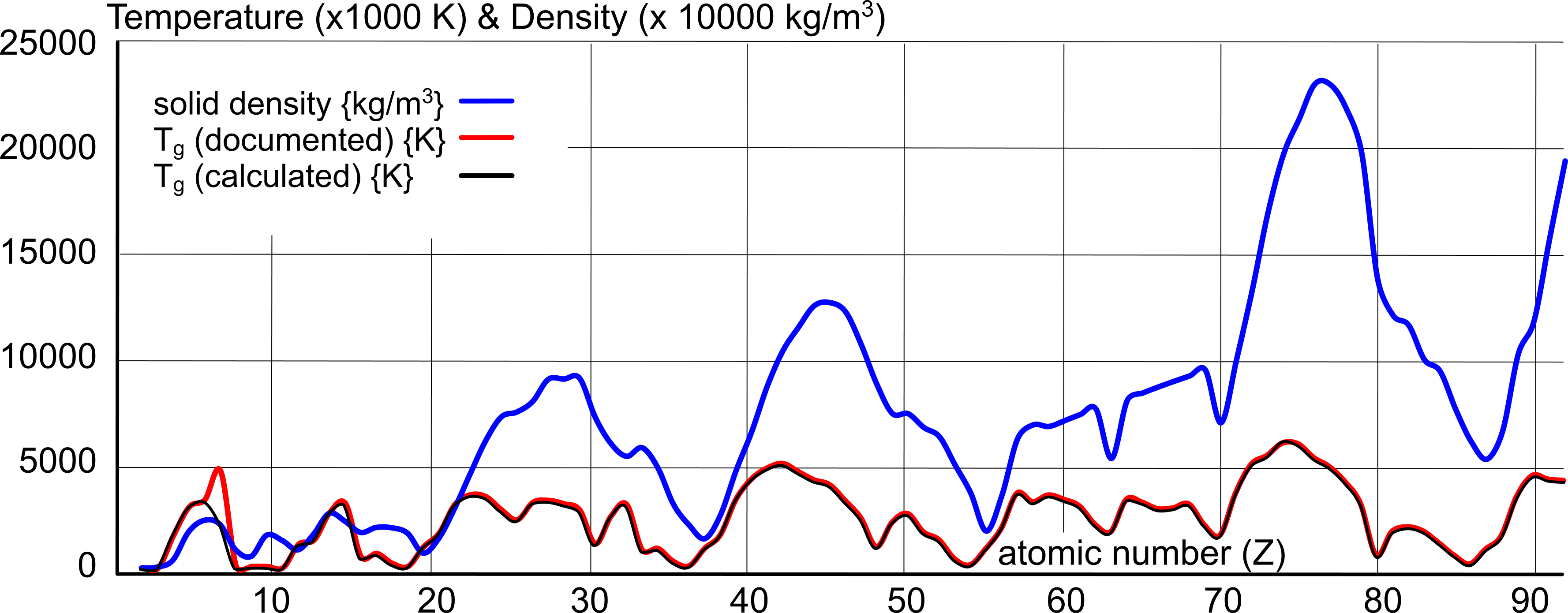

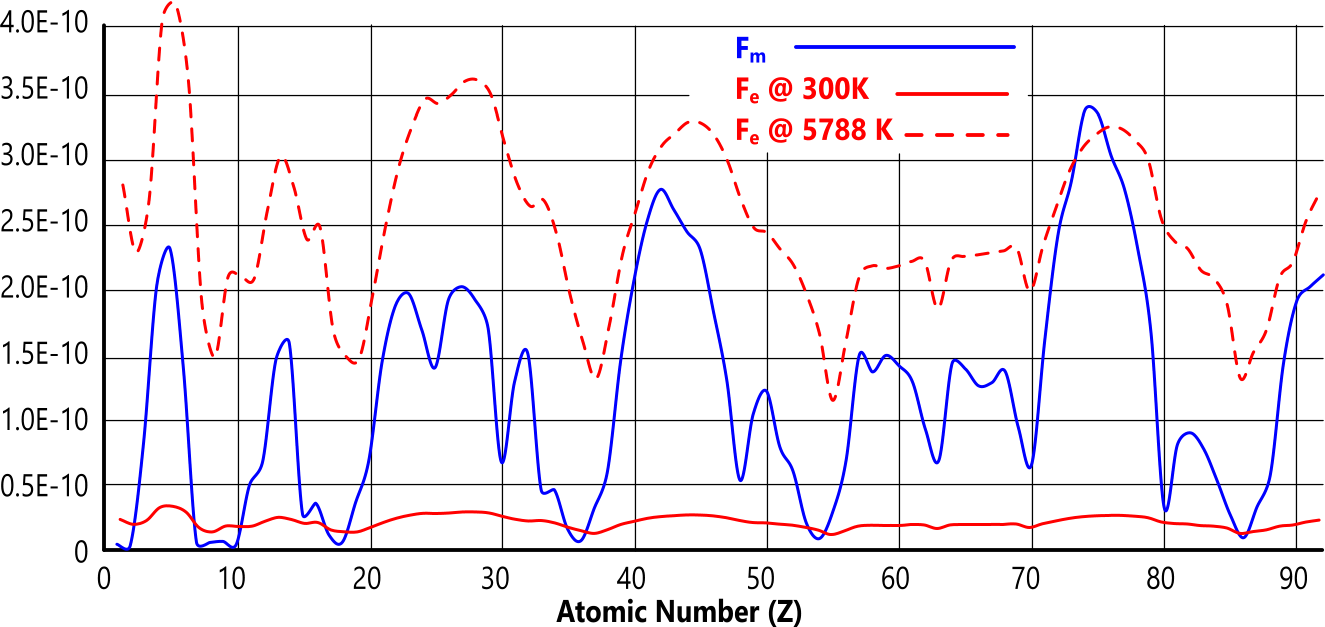

{Keith Dixon-Roche © 17/04/18}This work was initiated due to the discovery that a direct relationship appears to exist between the density of matter and its boiling point, as can be seen in Fig 1.

Its purpose is to answer the following question:

Can the Newton-Coulomb atomic model be used to predict the properties of elemental matter using mathematics?

In this context, 'matter' is the term used to describe a collection of pure elements in their natural state at any temperature and/or pressure. Same-element matter refers to that in which all the atoms have the same atomic number. All these calculations refer to same-element matter.⁽¹⁾

The state of matter refers to its condition; viscous or gaseous; the only two conditions that exist for all matter.

The state of matter is entirely dependent upon its inter-atomic forces, from which we can predict all of its properties accurately using mathematics. In other words, we should no longer need to rely on documented data, which usually varies (sometimes significantly); most sources simply copy data from other sources - that may or may not be reliable - without verification.

Viscous

The term 'viscosity' describes all and/or any matter when adjacent atoms are attracted to each other in solid or liquid form, and refers to the resistance in adjacent atoms to slip - plastically, as in plastic stress - relative to each other; Fₘ>Fₑ.

Liquid matter is no different to solid but the inter-atomic electrical separation force (Fₑ), which varies with temperature, is sufficient to reduce the effect of the attractive magnetic force (Fₘ) whereby slip between adjacent atoms occurs with little resistance (low viscosity). What we understand as 'solid' matter is simply that with a very high viscosity, you can still cause its atoms to slip by applying greater (than for liquid matter) force.

Solidity refers to a body's ability to maintain its shape under the prevalent ambient conditions; gravitational acceleration, atmospheric pressure, etc. It will differ in all matter throughout the universe, for example, here on Earth and on our moon.

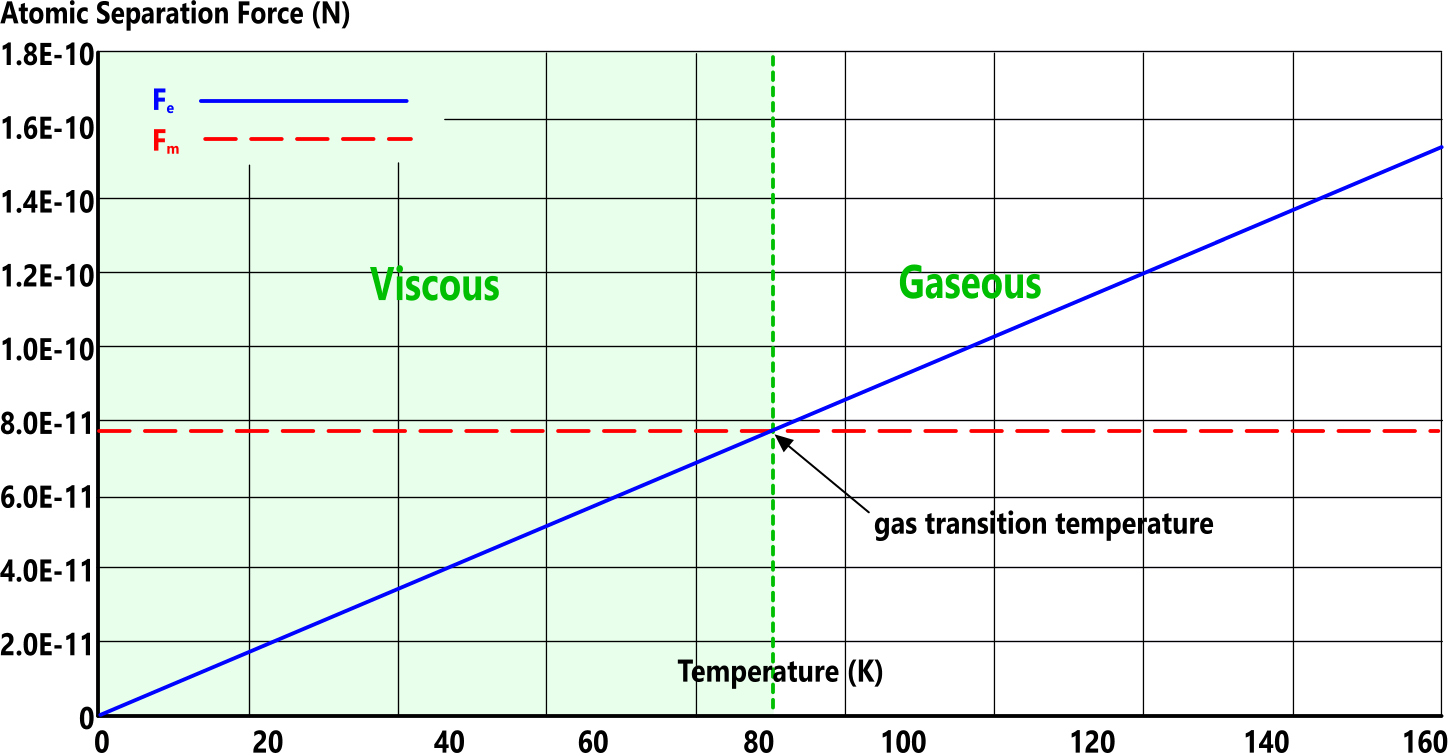

The density of viscous matter is [predominantly] constant because magnetism, which is the dominant force (Fₘ), remains constant at any temperature (Fig 2).

Gaseous

Gaseous is the term we use to describe matter when its atoms repel each other; i.e. when the electrical [charge] force of repulsion (Fₑ) is dominant.

This electrical force (Fₑ) is due to the positive electrical charge held in the nucleic protons, which varies with temperature (Fig 2).

As a gas, the force between adjacent atoms (F = Fₘ-Fₑ) is negative because Fₑ is greater than Fₘ, therefore, viscosity should not exist. However, at temperatures just above gas transition, magnetic attraction (Fₘ) is still evident and responsible for the resistance in bodies travelling through an atmosphere; atmospheric drag.

Fact & Fiction

It has become clear that very little we see, hear and read concerning the state of matter is either accurate or true. For example:

1) There are only two 'states of matter', viscous and gaseous; atoms can only exist together or separately, they do not transform#.

2) The term 'fluid' is a misnomer as it unites two disparate conditions; viscous and gaseous. All liquids are in a viscous state, gases are not.

3) There is no such property as the 'melting point' of matter. All matter will flow when it can no longer hold its shape under the influence of gravity. In other words, the 'melting point' of any matter will vary throughout the universe.

4) Protons, which constitute more than 99% of what is commonly referred to as hydrogen, cannot liquify due to their positive [proton] electrical charges; they can only repel each other. Only as hydrogen, deuterium or tritium (containing one or two neutrons respectively) can this occur⁽³⁾.

5) Refer to our elemental data web-page for the dispasrity between documented values of elemental densities and temperatures.

Refer to our experiences on this subject.

The highest energy (e.g. temperature {Ṯ} or electro-magnetic {EME}) in any atom occurs in the proton-electron pairs whose electrons are orbiting in shell-1. It is these atomic proton-electron pairs that define the interaction between elemental atoms. All the following calculations are therefore based upon the performance of these proton-electron pairs, whose electrons are orbiting in shell-1, and designated in the calculations with the sub-script '1'; e.g. PE₁, KE₁, etc.

Temperatures and Densities

The temperature (Ṯ) we measure in matter is the EME generated by the proton-electron pairs (2-off#) whose electrons are orbiting in shell-1; the atom's innermost shell (Ṯ₁).

# All hydrogen atoms have only one orbiting electron in shell-1; all other atoms have two.

Density (ρ) is the sum of atomic masses contained in a unit volume, which, as explained above, does not vary in viscous matter due to the dominant constant magnetic [field] forces.

However, this is not strictly true; density does vary with temperature - but only slightly - due to changes in its lattice structure, together with the reduction in relative inter-atomic forces (δF = Fₘ - Fₑ) as a result of changes in electrical [charge] repulsion between adjacent neucleic protons, which varies linearly with temperature.

The properties of same-element matter at room temperature used in the following calculations and plots are listed in Table 1:

Ṯg refers to documented boiling temperature (K) of the elements.

ρ refers to documented viscous density (kg/m³) of the elements,

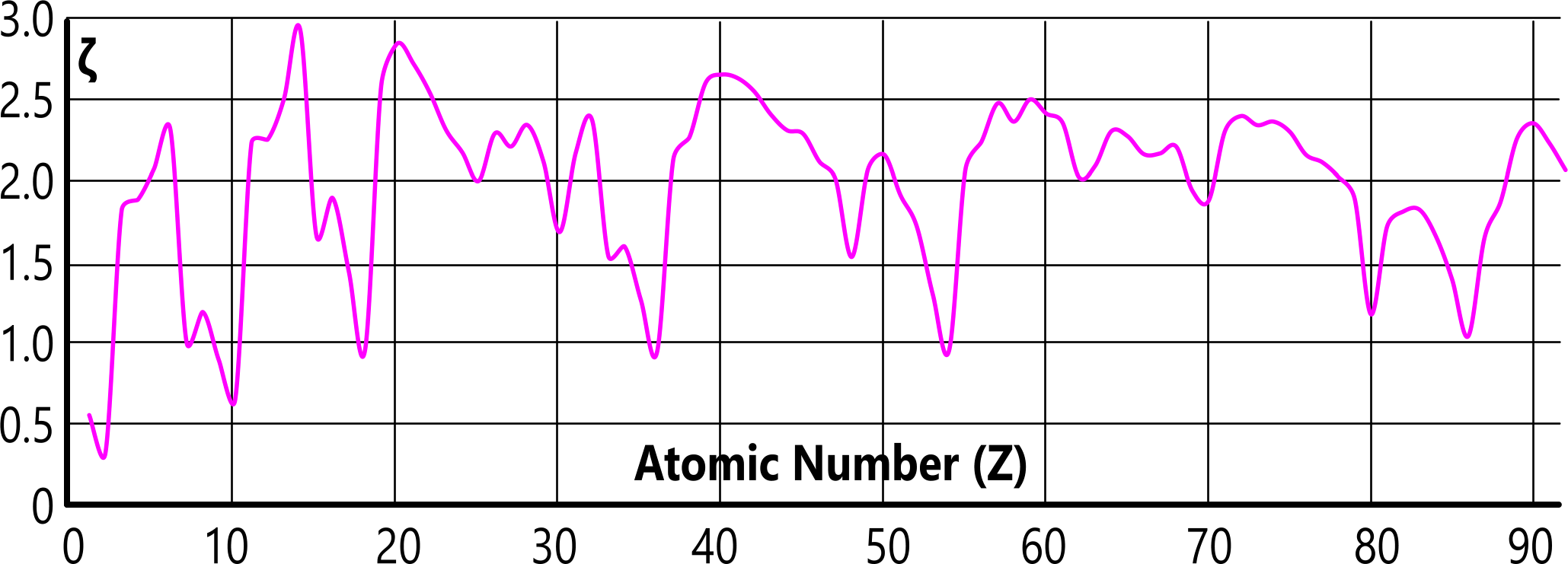

ζ refers to the lattice factor that must apply if the documented values are correct.

Fₑ refers to the inter-atomic electrical charge force {N) of repulsion between adjacent atoms in elemental matter at a temperature of 300K,

Fₘ refers to the inter-atomic magnetic field force {N) of attraction between adjacent atoms in elemental matter at a temperature of 300K,

Note: inter-atomic pressure; p = F/d²

It is important to understand that 'boiling point' is the temperature at which matter vapourises. It remains in a viscous state; globules suspended in atmospheric gases. Vapourisation requires the presence of an atmosphere.

Gas transition temperature is that at which atoms repel each other; every atom (or molecule) exists as an individual entity.

These conditions do not always occur at the same temperature and pressure as an element's boiling point.

Heat Transfer Constant (Y)

Question: To what does the heat transfer constant apply in atomic physics?

@ 293K ...

The potential energy in a proton-electron pair (PEₚₑₚ):

PEₚₑₚ = mₑ.v² = 3.940430E-20 J

PEₚₑₚ/Y = 4.045309E-21 J

And the potential energy between adjacent atoms in elemental matter (PEₑₘ):

pₑₘ = Rᵢ.Ṯ.ρ/(RAM/1000) = 8.7390993E+07 N/m²

PFₑₘ = Rᵢ.Ṯ.ρ/(RAM/1000) . d² = 1.117821E-11 N

PFₑₘ = Rᵢ.Ṯ.mₐ/d³/(RAM/1000) . d² = 1.117821E-11 N

PFₑₘ = kB.NA.Ṯ.mₐ/d³/(RAMRAM/1000) . d² = 1.117821E-11 N

PEₑₘ = kB.NA.Ṯ.mₐ/d³/(RAM/1000) . d³ = 4.045309E-21 J

PEₑₘ = kB.NA.Ṯ.mₐ/(RAM/1000) = 4.045309E-21 J

NA.mₐ/(RAM/1000) = 1.0 (all elements)

PEₑₘ = kB.Ṯ . 1.0 = 4.045309E-21 J

PEₑₘ = kB.Ṯ = 4.045309E-21 J

Therefore, potential; energy, force and pressure between adjacent atoms in any elemental matter are all less than those in a proton-electron pair (at the same temperature) by the heat transfer constant (Y).

Because PEₑₘ = kB.Ṯ = PEₚₑₚ/Y, and because pₑₘ = Rᵢ.Ṯ.ρ/(RAM/1000) is the universally accepted formula for calculating the pressure in a gas, i.e. the repulsion between adjacent atoms, we know that 'Y' must apply to the electrical force of repulsion (Fₑ) between adjacent atoms in elemental matter ...

Fₑ . d/R₁ = Fₚₑₚ/Y

... rather than the magnetic attraction (Fₘ):

Fₘ = μₒ.ξₘ . I₁² . (2π)² . (R₁/d)³ . RAM.mₙ/mₚ / ζ³ = ρ.hₑ² / ζ³

The question is, why does the heat transfer constant apply to elemental matter and not to the proton-electron pair?

We must not forget that the potential energy in a proton-electron pair is dynamic, whilst the potential energy between adjacent atoms is static, and 'Y' is dependent upon the dynamic ratio (Y = ³√[½.ξᵥ]), and 'd' is the cube-root of the volume of elemental matter (d = ³√[mₐ/ρ]).

Inter-Atomic Pressures & Forces

The inter-atomic forces in all matter - both viscous and gaseous - are either repulsive (Fₑ) or attractive (Fₘ). The forces of repulsion push adjacent atoms apart and the forces of attraction hold them together. Fig 2 shows how this works.

These forces are are generated by an atom's shell-1 proton-electron pairs. 'Fₑ' is generated by the proton's electrical charges (e'), and 'Fₘ' is the magnetic field generated by its shell-1 proton-electron pairs.

These forces are responsible for generating inter-atomic pressures that may be calculated using the well-established and universally accepted PVRT formula thus:

pₑ = Rᵢ.Ṯ.ρ / (RAM/1000)

where pressure: pₑ = Fₑ/d²

However, all of the following formulas also provide exactly the same value for any temperature (Ṯ):

pₑ = -PE/Y / d³

pₑ = kB.Ṯ / d³

pₑ = ρ.kB.Ṯ / mₐ

pₑ = PEₙ/Y . (Ṯ/Ṯₙ) / d³

confirming the Newton-Coulomb atomic model.

The inter-atomic force of repulsion due to electrical charge is therefore:

Fₑ = pₑ.d² = PE₁ / Y.d = kB.Ṯ₁ / d

Refer to our web page for definitions of earth's atmospheric inter-atomic pressures and forces @ sea-level (where; pₐₜₘ = pₐᵢᵣ and Fₐₜₘ = Fₐᵢᵣ)

Note: inter-atomic force due to magnetic field:

Fₘ = μₒ.ξₘ/ζ³ . I₁² . (2π)² . (R₁/d)³ . RAM.mₙ/mₚ = ρ.hₑ²/ζ³

Inter-atomic forces (including atmospheric effect):

due to electrical charge: Fₑ = d².(pₑ - pₐₜₘ)

due to magnetic field: Fₘ = ρ.hₑ² / ζ³

Inter-atomic pressure due to magnetic field:

pₘ = Fₘ/d²

The difference between the two (δp = pₑ - pₘ) is the active inter-atomic pressure:

if δp<0 the matter will be viscous;

if δp=0 the matter will be at gas transition temperature;

if δp>0 the matter will be gaseous.

Gas-Transition Temperature

Gas transition temperature occurs when the electrical and magnetic forces are equal (Fₑ=Fₘ) (Fig 2)

The temperature at which this condition occurs here on Earth, depends upon the partial pressure of same-elemental atoms in the atmosphere.

Fig 1 reveals an undeniable relationship between the magnetic and electrical inter-atomic forces and the boiling point of the elements.

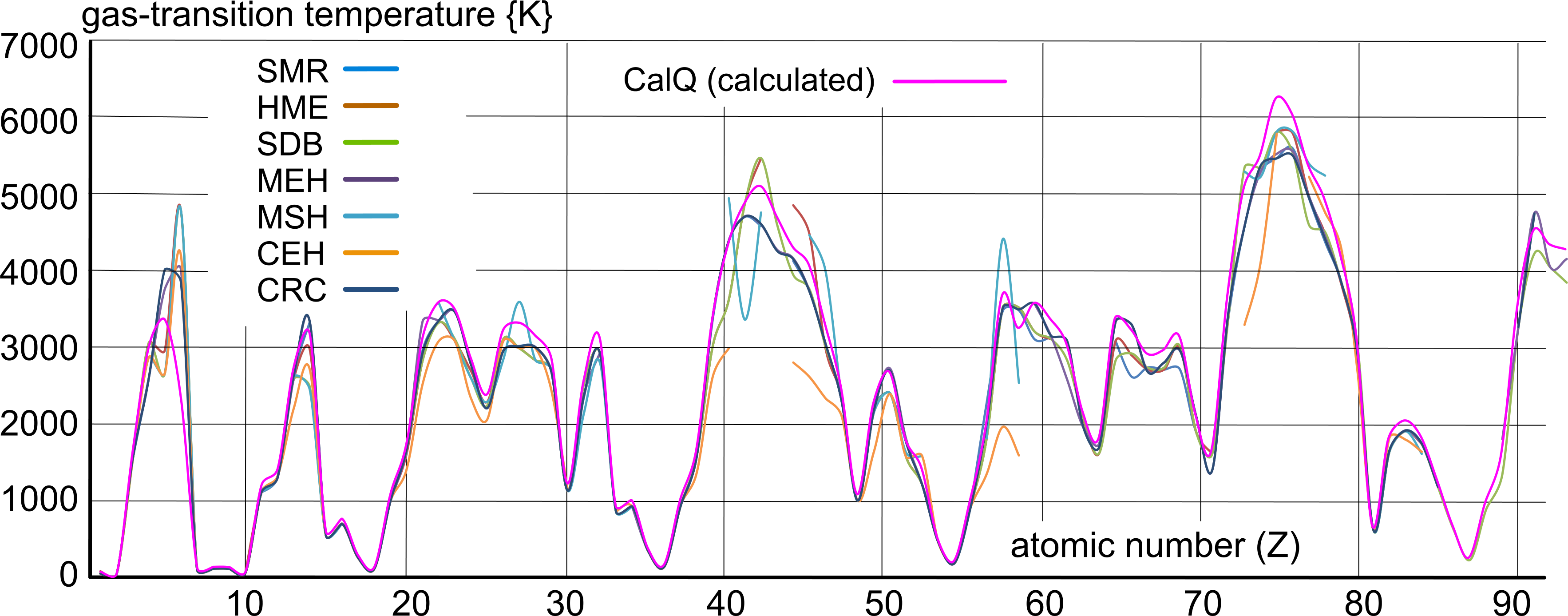

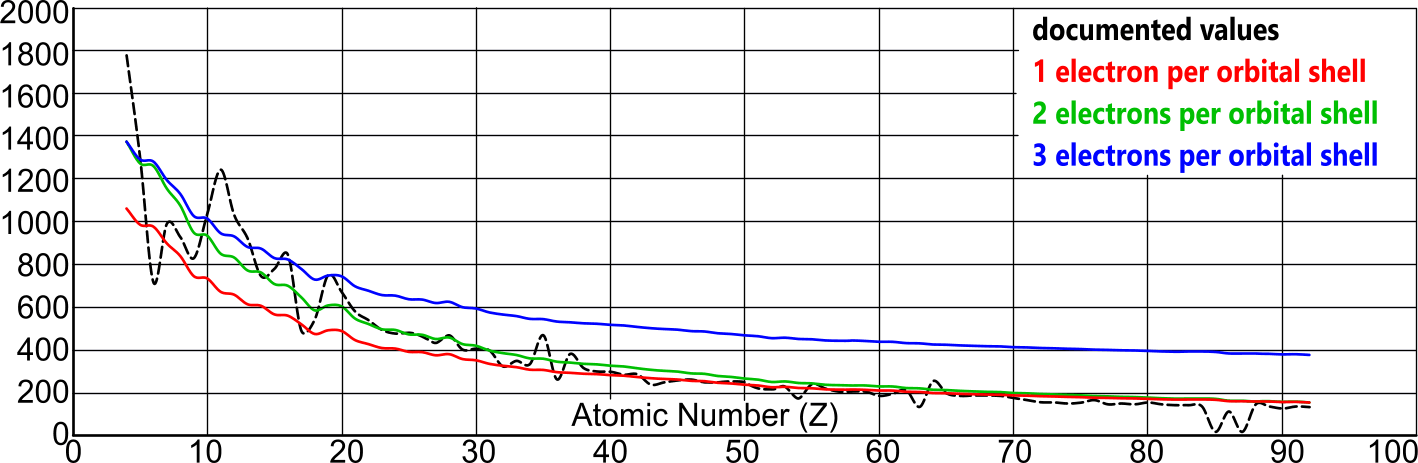

Whilst documented values for the boiling-point of elemental matter are at best 'analogous', they do reveal a definite pattern (Fig 3). Their inconsistency is due to poorly controlled experimentation procedures along with the long-standing custom of copying data from unreliable sources.

However, the calculated values (CalQ), which are mathematically consistent, also follow the same pattern.

The density and gas-transition temperature of elemental matter is explained in detail on our Density & Temperature web-page.

Pressure

The inter-atomic pressure in all matter - in both viscous and gaseous states - is due to the electrical [charge] forces of repulsion between adjacent atoms, which varies linearly with temperature.

In pure elemental matter, this pressure is total.

In a mixture of elements, this pressure between each same-elemental matter is referred to as a partial pressure.

The total pressure in a mixture of numerous same-element matters is the sum of all the partial pressures. This condition applies to all matter; both viscous and gaseous.

At first sight, Dalton's law and partial pressure theory appear to conflict.

If as Dalton states; each gas in a mixture of gases should be treated independently, the pressure in a container of mixed gases should be the maximum individual pressure. But this is not the case; partial pressure theory tells us that the total pressure is the sum of the individual gases.

This anomaly may be explained as follows:

Partial Pressure

All the atoms in a mixture of atoms will repel all other atoms but differently, because their nucleic arrangements differ. Inter-atomic repulsion between atoms with different atomic numbers (Z) will therefore be extant but random. I.e. you must add all pressures together to find the total pressure.

Dalton's Law

All same-element atoms contained in a mixture of different atoms will repel all other atoms of the same atomic number uniquely, according to their nucleic arrangement, maximising their separation distances, and thereby filling their container. This is why you must treat each same-element matter - within a mixture - individually; i.e. just as if the same-element atoms occupied the container alone. The resulting pressure will be a partial pressure.

Lattice Structure

The lattice structure of every element originates in - and is defined by - its nucleic protons, and is replicated in the atomic arrangement in all elemental matter in both gaseous and viscous states.

I.e. same element atoms always attract and repulse in a similar pattern to that held by the protons in an atom's nucleus. This pattern is what we today refer to as a lattice structure that depends upon the atom's nucleic arrangement.

We designate these lattice structures as; face-centre cubic, body-centre cubic, tetrahedra, close-packed hexagonal, etc. but they are not quite so simple. Whilst a particular group of atoms may resemble a single structure, they will not be identical; every lattice structure differs from every other (refer to Table 1 above).

This pattern applies to all same-element matter in both viscous and gaseous form, and is therefore responsible for partial pressure theory.

The lattice factor is calculated as follows for documented values:

ζ = ³√[ (ρ.hₑ²/d²) / (Rᵢ.Ṯ.ρ/(RAM/1000) - pₐₜₘ) ]

where;

ρ = the density of the elemental matter.

Ṯ = the temperature of the elemental matter.

pₐₜₘ = atmospheric pressure.

Fig 4 shows the relationship between the density and gas-transition (ρ/Ṯg) of elemental matter, and its lattice factor (ζ).

In other words ...

... if you pour two or more molten elements together, say; copper and nickel, they would coalesce independently, as same-element matter, despite the fact they are both FCC and only one atomic number apart (29 and 28 respectively)#.

That this division occurs naturally, is evidence that elemental lattice structures are not as we suspect, but unique for each and every element, which is borne out by the unique lattice factors (Fig 4).

In fact, the separation of all elements as they transpose through their a viscous states is due to their unique nucleic arrangements, that differ according to their neutronic ratios (ψ), all of which are also unique.

This means that whilst we currently compartmentalise elemental structures; FCC, BCC, HCP, Tetra, etc. this is only an approximation. Whilst some elemental structures may look the same, they are actually similar; not identical. Every element has a different lattice structure.

# alloys are formed by forcing more than one same-element matter together when viscous and pliable.

Inter-Atomic Spacing

An average value for atomic spacing (d), which is due to inter-atomic forces, may be found from its density and atomic mass; d = ³√[mₐ/ρ].

Whilst 'd' will vary with direction (orientation) in same-element matter, it tends to be similar in any direction in amorphous matter.

Calculations

Density

The density of elemental matter may be calculated like this:

ρ = mₐ/d³

where; mₐ is the atomic mass, and the mean separation distance between two adjacent atoms (d) in a perfect crystal of any same element matter may be calculated thus:

d = ³√[mₐ/ρ]

The viscous density of elemental matter may be considered reliable because it does not vary (significantly) with ambient conditions. It can therefore be measured with a good degree of confidence.

Gas density is less reliable because it depends upon the purity of the elemental gas. But in a pressurised container of pure elemental matter, it too can be measured with reasonable confidence.

The density of gaseous matter in an unchanging container will not vary with fluctuating pressure and/or temperature.

Refer to our comparison between various sources.

Temperature

Temperature is a term that has been given to the EME radiated by a proton-electron pair. It can be calculated like this:

Ṯ = PE / Y.kB = X.v²

where;

Ṯ is the temperature of EME radiated by the proton-electron pair {Kelvin}.

PE is the potential energy in the proton-electron pair {Joules}.

v is the orbital velocity of the electron {m/s}.

There are two principal temperatures for all matter …

… 'boiling point'; is the temperature at which matter vaporises,

… 'gas-transition'; is the temperature at which all adjacent atoms repel each other,

these temperatures are not always the same.

Because these temperatures are dependent upon ambient conditions, that may or may not be carefully monitored in experimental evaluation, you cannot rely on generally available documented data, which varies considerabley between sources.

Refer to our comparison between various sources.

Pressure

The internal pressure between atoms can be calculated in elemental matter, in both viscous and gaseous states, if its density (ρ) and measured temperature (Ṯ₁) are both known, using a universally known and accepted formula:

p = Rᵢ.Ṯ₁.ρ / (RAM/1000) {kg.(m/s)² / K.mole . K . kg/m³ . mole/kg = kg.m/s² / m² = N/m²}

But the following formulas also generate exactly the same result, together with the correct units:

p = PE₁ / Y.d³

p = kB.Ṯ₁ / d³

p = ρ.kB.Ṯ₁/mₐ

all of which, ultimately break down to one equivalent formula;

p = mₑ.c² / Y.d³ . Ṯ₁/Ṯₙ

and then to;

p = PEₙ/Y . Ṯ₁/Ṯₙ / d³

Verification:

The Newton-Coulomb atomic model is again verified here because;

Rᵢ.Ṯ₁.ρ / (RAM/1000) = PE₁ / Y.d³ = PEₙ/Y . Ṯ₁/Ṯₙ / d³

where 'PE₁' and 'PEₙ' refer to circular electron orbits and 'Ṯ₁' refers to shell-1 (measured) temperature.

The density of a gas depends entirely upon the mass of the atoms in its container and its temperature, i.e. its pressure.

Therefore, calculating the properties of a gas are entirely arbitrary unless you are provided with its temperature and its pressure or its density; if you have any two values, you can calculate the other using the above formulas.

Electrical Charge Force of Repulsion (Fₑ)

The mean inter-atomic force of repulsion in elemental matter may therefore be defined using any of the following formulas, all of which give exactly the same result and the correct units:

Fₑ = p.d²

Fₑ = p . ⅔√[mₐ/ρ]

Fₑ = -PE₁ / Y.d

Fₑ = mₑ.c² / Y.d . Ṯ₁/Ṯₙ

Fₑ = PEₙ/Y . Ṯ₁/Ṯₙ / d {kg.m²/s² / m = kg.m/s² = N}

and which vary with temperature (Ṯ₁).

Magnetic Field Force of Attraction (Fₘ)

Inter-atomic magnetic field force of attraction may be calculated thus:

Fₘ = μₒ.ξₘ/ζ³ . I₁² . (2π)² . (R₁/d)³ . RAM.mₙ/mₚ (Joseph Henry)

where; I₁ is the internal current generated by the atom's shell-1 electrons and R₁ is their orbital radius

or;

Fₘ = ρ.hₑ²/ζ³ (Isaac Newton)

The above calculation is for a gas released into a vacuum. But in an atmosphere;

Fₘ = Fₘ + Fₐₜₘ

which does not vary with temperature.

When 'Fₑ' exceeds 'Fₘ', the elemental matter will exist as a gas, otherwise it will be viscous.

At gas transition temperature (Ṯg):

Fₑ = Fₘ + Fₐₜₘ

Specific Heat Capacity (SHC)

The specific heat capacity for all atoms, may be calculated thus; SHC = ΣKE / Ṯ.Y.mₐ

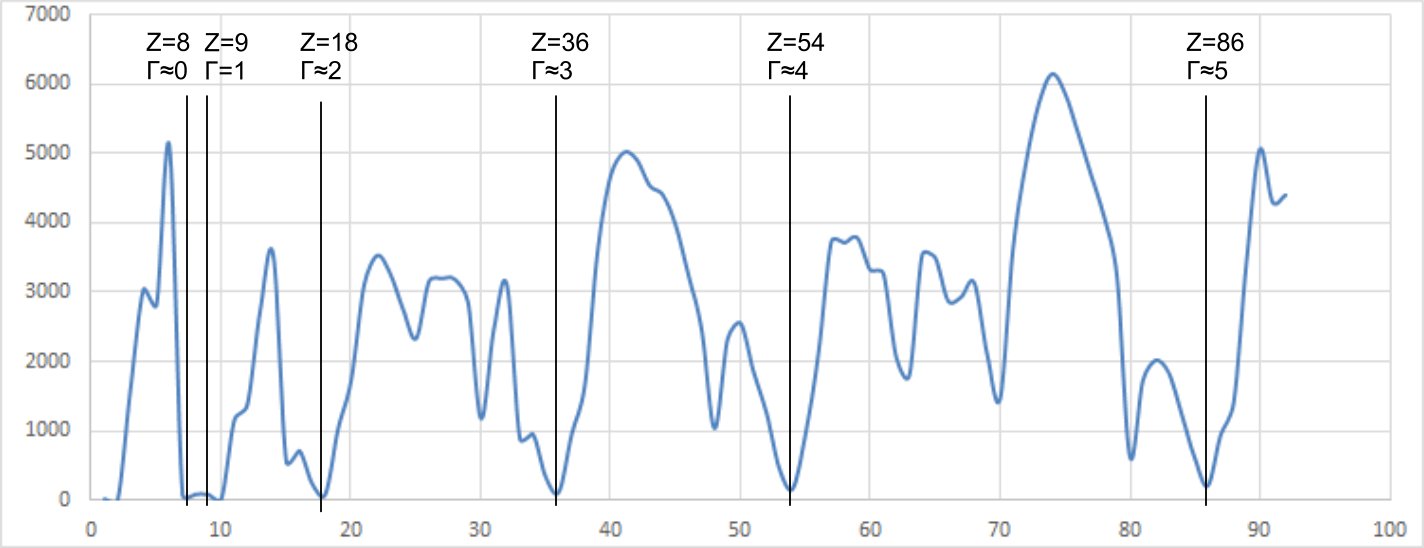

where ΣKE is the sum of the kinetic energies in all the proton-electron pairs in any atom, and mₐ is the atomic mass (Fig 6).

Fig 6 confirms the Newton-Coulomb atomic model with two electrons per orbital shell.

Properties

The inter-atomic pressure (p) generated by these forces (Fₘ & Fₑ) can now be used to predict various properties of matter, which when taken along with the relationship between neutronic ratio (ψ) and matter density (ρ) (Fig 3), it is evident that all the physical properties of matter can be predicted from an atom's neutronic ratio and its atomic mass. For example:

F = Fₘ-Fₑ

However, we now know that the properties of viscous elemental matter may also be calculated using the PVRT formulas.

Viscosity

The dynamic viscosity (μ) of all elements - at a specified temperature - can be calculated thus;

μ = p / Γ.ƒ (see Noble Gases below for a definition of 'Γ')

By way of comparison: the documented value for liquid mercury @ 293K is; μ = 0.001526 kg/m/s whereas the calculated value is; μ = 0.00165282 kg/m/s

Note: the kinematic viscosity (ν) may be derived thus; ν = μ/ρ

Surface Tension

Surface tension is the linear force holding adjacent atoms together. It is measured in units of N/m and can be calculated thus;

γ = p.Y.d

By way of comparison: the documented value for liquid mercury @ 293K is; γ = 0.465 N/m whereas the calculated value is; γ = 0.4527 N/m

Yield Stress

Fig 7. Inter-Atomic Lattice Arrangement

The yield stress of elemental viscous matter is simply a measurement of the internal pressure between atomic planes;

σᵧ = p

By way of comparison: the documented value for iron @ 293K is; 1.5E+08 < σy < 5.52E+08 N/m² whereas the calculated value is; σy = 3.40561E+08 N/m²

Elastic Modulus

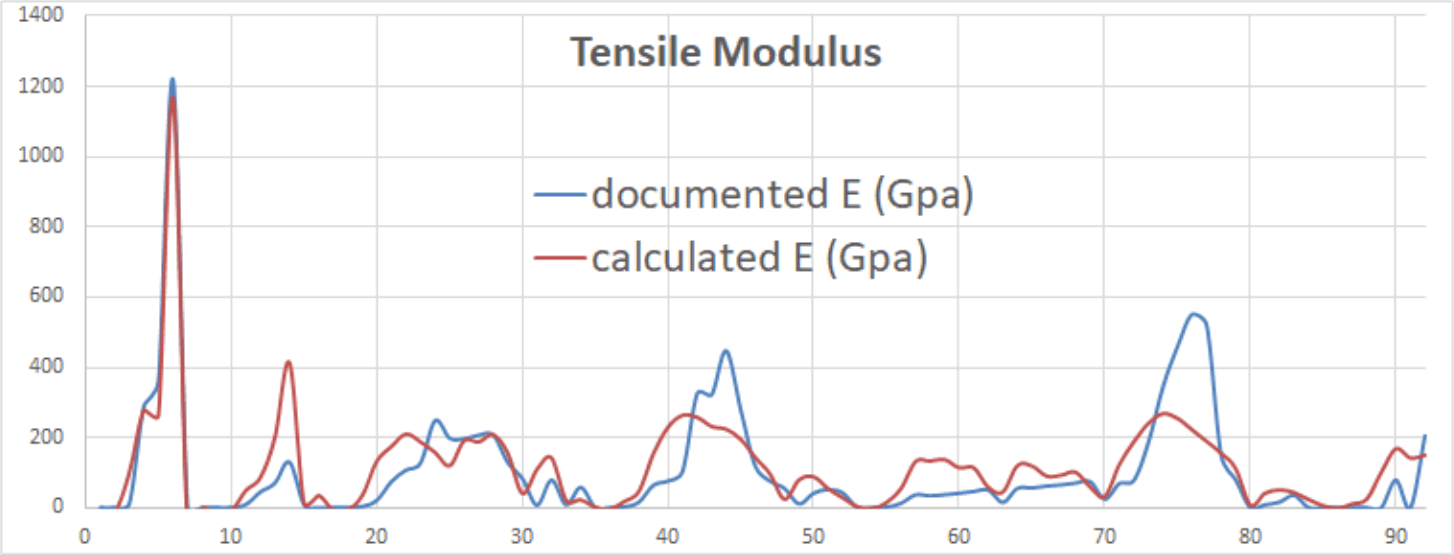

Young's modulus (E) for each element at a specified temperature may be determined thus (Fig 7);

E = p . (d/(h.sin(60°))³

where h = d.(1-sin(60°))

By way of comparison: the documented value for iron @ 293K is; E = 1.965E+11 N/m² whereas the calculated value is; E = 2.182E+11 N/m²

Noble Gases

Fig 8 reveals the noble gases based upon the neutronic ratio, which may be calculated thus;

Γ = 9.(ψ -1)

the noble gases occur when Γ is at or close to an integer; 1 to 5

Atmospheric Drag

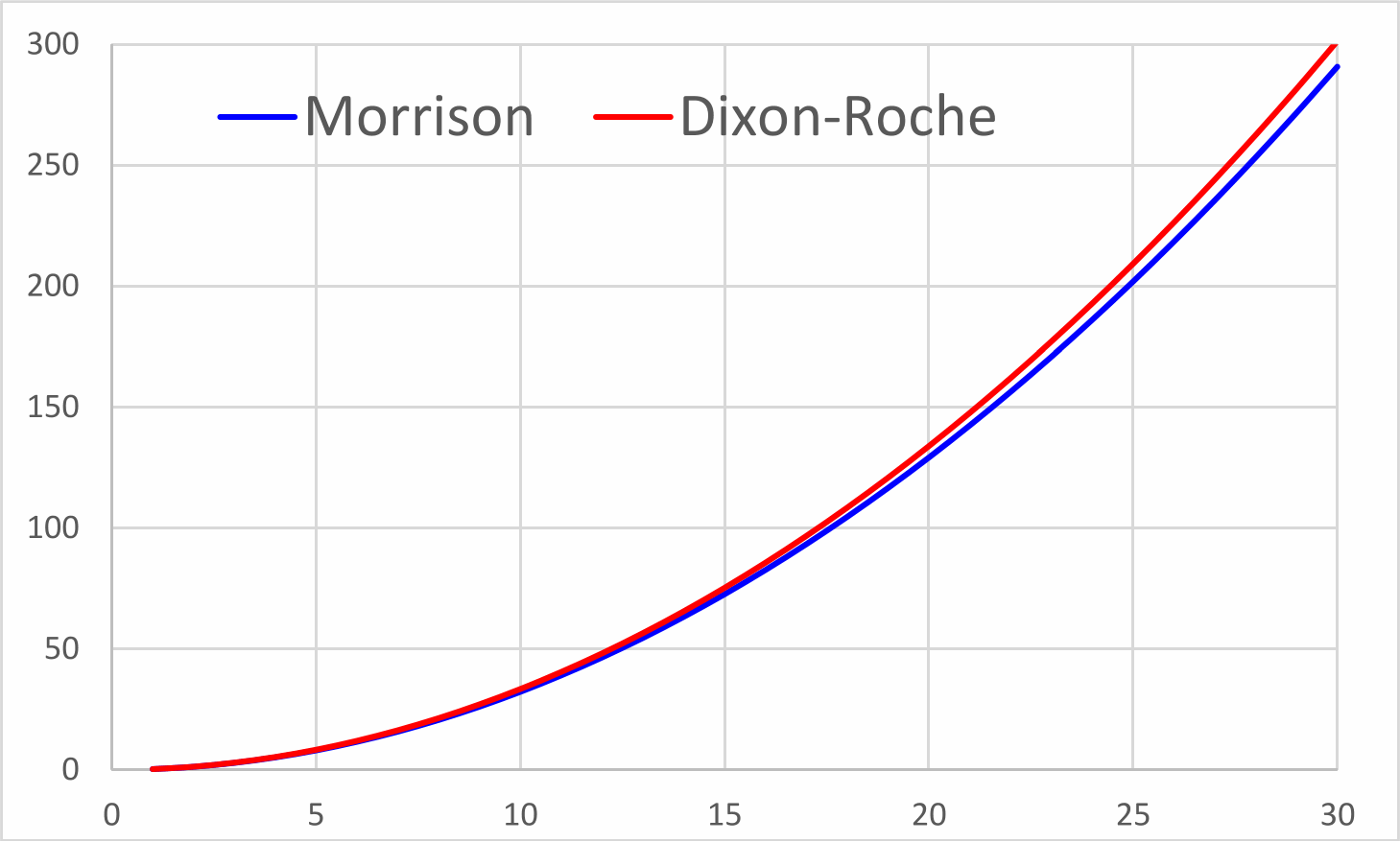

The current method for calculating the resistance (force) generated in a body travelling through a gas was established by J. R. Morrison et. al.

However, because the magnetic [attraction] force (Fₘ) between adjacent atoms is responsible for the drag on bodies passing through an atmosphere, the Newton-Coulomb atomic model can now be used to determine this resistance based upon relative velocities and energies thus:

F = hₑ.ρ.ψ . N° . (vd/vₐ)² . (PEₙ/-PE₁)

where;

A = cross-sectional area

ρ = gas (e.g. air) density

N° = number of atoms in contact with the body (= A / π.Rₛ²)

vd = relative velocity between body and gas

v₁ = electron velocity in shell-1 (gas-atom)

PE₁ = potential energy proton-electron pair in shell-1 (gas-atom)

Whether or not inter-atomic magnetism is the cause of atmospheric drag, the above calculation makes this argument extremely compelling; yet again validating this atomic model.

The Molecule

The molecule (and atomic bonding) is the next step, which can also be solved mathematically using the same atomic forces.

Whilst Keith Dixon-Roche knows how to solve this problem,

due to the responses he has received as a result of his scientific discoveries and their possibilities, he has decided to leave this work up to you,

but he is willing to give you a hint:

'atomic and matter densities react differently with varying temperature;

e.g. the density of an iron atom @ 300K is 0.007533336 kg/m³ but the density of its matter is 7870 kg/m³.

That atomic density increases with rising temperature as matter density decreases, is a clue as to the functioning of chemical bonding; electron charge sharing.'.

Oh yes! and there is no such thing as co-valent bonding. Such bonding between atoms is due to quite a different function.

He wishes you luck.

Notes

- Refer to our elemental data web-page..

Note: the value included in Elements was taken from the most reliable documented source at the time. However, whilst CalQlata's calculated value may not be exact, it clearly demonstrates that none of the documented values can be counted upon. - The density of solid boron is said to be 2320 kg/m³, but a reliable technical source (page 5) states that the specific gravity of liquid boron varies between 1.32 and 1.36 but does not state the associated temperatures or pressures.

- H⁺, which represents about 99.997% of all atmospheric hydrogen, can never coalesce as a liquid because it possesses a positive charge and generates no magnetic field. However, the inability of hydrogen atoms (H) to attract other hydrogen atoms (H) in viscous form is currently hypothesis, based upon their positive proton electrical charges. If, however, at a sufficiently low temperature, their attractive magnetic forces (Fₘ) are greater than their repulsive electrical forces (Fₑ), a liquid state may exist.

Further Reading

You will find further reading on this subject in reference publications(69, 70, 71 & 73)